The Native Americans from the Sinixt tribe, the pioneers and settlers of the mining days, the members of the Russian Doukhobor religious community, the Japanese-born internees of World War II, the Vietnam conscientious objectors from the USA, the hippies of the 1970s, and the immigrants from all over the world have left their mark on the West Kootenays.

For more than 3000 years, the Sinixt tribe inhabited the region in permanent settlements. The Ktunaxa tribe of the East Kootenays came here temporarily to fish and hunt. Both tribes traveled lakes and rivers in uniquely shaped canoes. Waters rich in fish and forests with a variety of wild animals, edible plants, berries, mushrooms, and herbs secured their livelihood. The rock carvings at Slocan Lake, painted in ochre, provide evidence of trade with distant tribes.

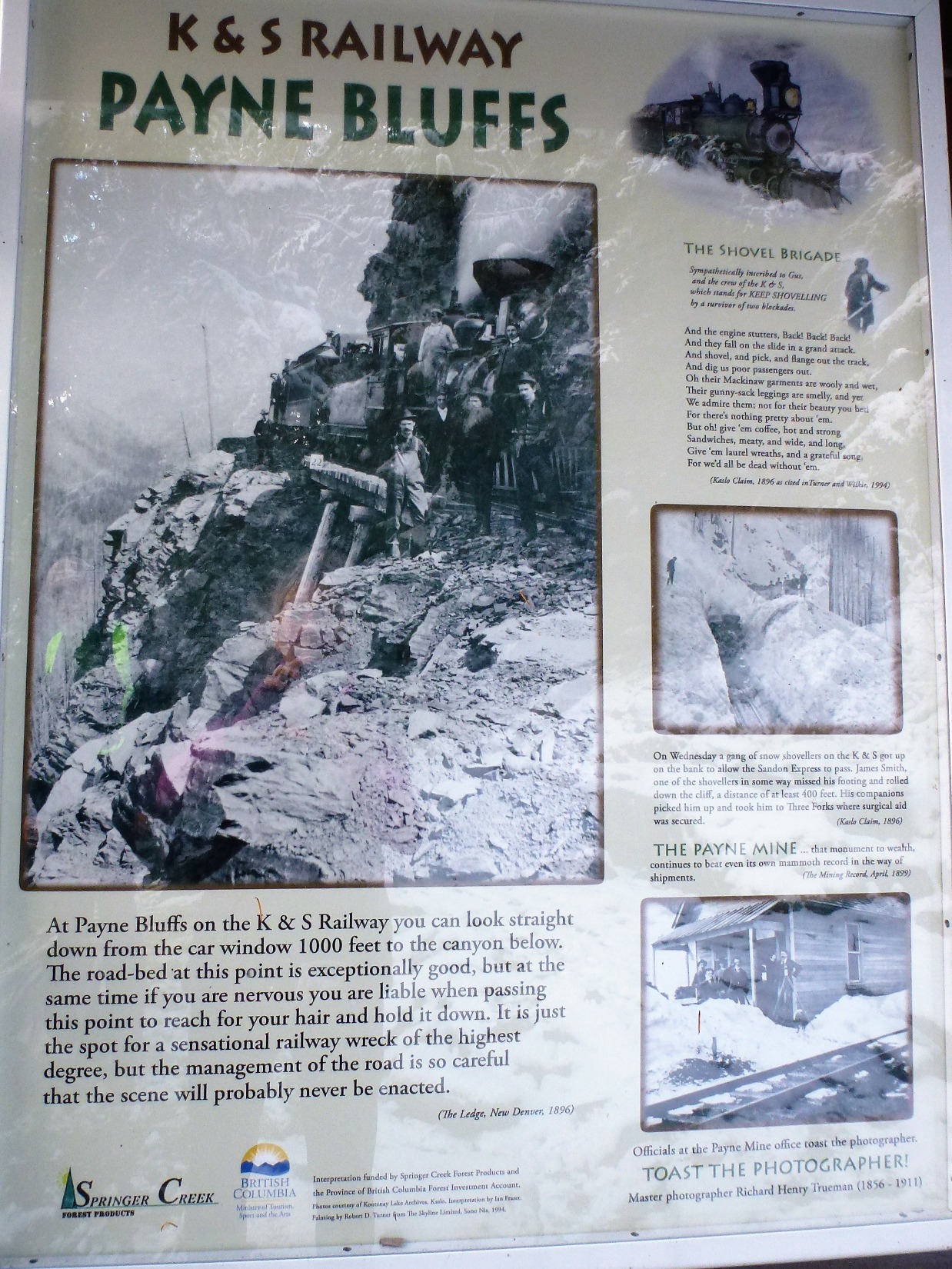

Findings of silver attracted the first white pioneers in the late 18th century. Mining towns like Silverton and Sandon sprung up overnight. Paddle steamers plied the lakes and railways were built in a race. At the end of the 19th century, the mining boom was over as quickly as it had come. Fortune seekers left the area, but settlers stayed.

But that short span of time had destroyed the livelihood of the First Nations. Forests were hunted empty, lakes and rivers fished empty. Smallpox and influenza viruses brought in by the whites severely decimated the indigenous population. The few survivors went to live with their tribesmen on a reservation in Colville, Washington. The border between the United States and Canada agreed in 1783 with the course of the 49th parallel, cut through the ancestral territory of the Sinixt. The small group that refused to leave the Slocan Valley was settled on a reservation at Arrow Lakes. With the death of their last tribe member in 1956, the Sinixt were declared extinct in Canada. It was only in 2021 that this decision was overturned by the judgment of the Supreme Court of Canada.

In 1899, 7,500 members of the Doukhobor community faith, persecuted in Tsarist Russia, found asylum in BC. They lived in almost monastic communities with no private property. and began cultivating the land for growing fruit and vegetables. The living communities no longer exist, but their descendants maintain their language and customs. In Castlegar, the Doukhobor Museum and Zuckerberg Island tell their stories.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, thousands of people of Japanese descent were declared potential spies in the USA and Canada. Both countries began internment that lasted until many years after the war ended. In BC, 125,284 people were exiled to camps in remote inland regions, to New Denver, Sandon, and Lemon Creek. In the Slocan Valley. In New Denver, the Nikkei Museum tells their stories. Some of the interned people stayed in the area after the war and their cultural influence is still felt today.

Between 1965 and 1975, around 125,000 anti-Vietnam opponents sought refuge in Canada to avoid military service and imprisonment as conscientious objectors. After President Carter’s amnesty in 1977, about half remained in Canada and most became citizens. They brought with them free thinking, a good education, political and social commitment, handicraft skills, and the independent lifestyle of the hippie movement. Their quest to live a simple life in harmony with nature is still alive in the Kootenays and is evident in many dedicated conservation groups.

The history of residential schools shows that Canada’s history is not without dark sides. The state-sponsored religious schools, under the brutal and misanthropic leadership of the Christian churches, were established after 1880 to educate and proselytize Indigenous children and integrate them into Euro-Canadian culture. The children were torn from their families by all means of violence and attempts were made to erase their cultural roots by forbidding their language and rites. These schools were cruel places filled with violence and starvation, disease and humiliation that many children did not survive. The last boarding school closed in 1996. Only recently, in 2021 and 2022, 1300 of unmarked children’s graves have been found. Many more are likely to follow. This has shaken the country deeply and triggered a discussion about reconciliation and reparation, which the Canadian state but also the Christian churches have to face up to.

Children from Doukhobor families belonging to the radical Sons of Freedom group also suffered a similar fate in BC. In the 1950s, under orders from the provincial government, police abducted children from their families and took them to a camp in New Denver. Many of these people are still suffering from the traumatic consequences and have recorded their fate in biographies that can be purchased in local bookshops.